Florante Aguilar’s interview at the Asian American International Film Festival’s New York premiere of HARANA. The original publication can be found here.

###

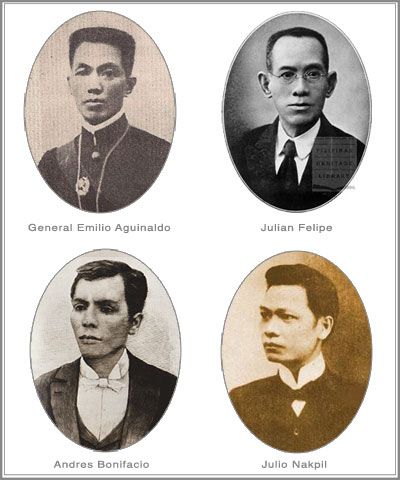

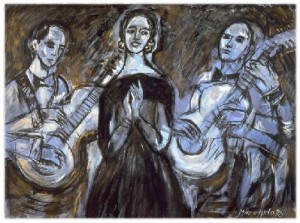

Harana is a long-abandoned Filipino courtship serenade, which originated in the Spanish colonial period. In this award-winning documentary, guitarist Florante AGUILAR returns to the Philippines from the US for the first time in twelve years to discover three of the last remaining harana masters: a farmer, a fisherman, and a tricycle driver. HARANA emotively weaves their performances to exemplify the past and present, the here and there, and the rural and urban.

CineVue: The film is first and foremost a roots-seeking story, or can be read as a confrontation/reconciliation with one’s roots. What is the importance of yearning and nostalgia of a so-called homeland in films like yours? What function does this serve in your story?

Florante Aguilar: I think this question is particularly astute because HARANA in its deepest level, is a love affair with the homeland. It is the innermost driving force of the movie. Being a musician, the only way I knew how to express that love is through music.

One of the things that we did not cover in the film is the fact that I left the Philippines in 1987 because I hated everything about my country – the politics, the rampant corruption, the over-reliance on religion, the hopelessness, etc. I felt that I could not live and belong in a culture like that. Inwardly, I renounced being a Filipino and left for the US ready to embrace the western culture.

But the death of my father forced me to return after 12 years of absence. And that’s when the reconnection happened. This time around, I saw the Phlippines in a different prism and I was suddenly in love with the Philippines. Suddenly, I felt like I belong.

So, it’s not nostalgia per se but rather the power of that transformation – from hate to love – that moved me to do it. Maybe it’s also an apology and an attempt to make amends for renouncing the homeland.

CV: Because of the power of music, the beautiful melody and the tenderness and sorrow in the voices of the singers, many would agree with the proverbial saying that “There are no languages required in a musical world.” How have you utilized music in your film? Could you describe how music has affected your creative processes (from preproduction to production to post-production)?

FA: During pre-production, all I had was this notion that these authentic harana practitioners or haranistas must still be around, very old, and living in far-flung provinces.

Musically, all I had were the remnants of harana music or songs I happened to know that survived through the ages. I heard them when I was growing up in the province and also through the pieces my mother played on the piano.

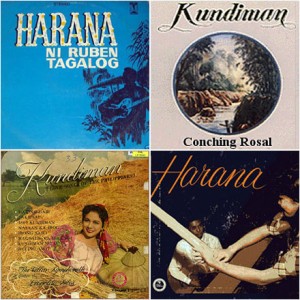

During my so-called transformation, I started playing harana which I arranged for classical guitar, resulting in three solo albums. But I also felt that this was just the surface, that there must be many more unheralded songs. I fantasized about unearthing a treasure trove of beautiful courtship music and forming an ensemble of authentic haranstas. Well, I wanted that fantasy to come true. And I determined to look for them in the provinces where harana was prevalent.

As we were traveling from province to province during the production shoot, there were points when I realized that I must be just fantasizing – that this search is just some romantic notion. And that if we did not find anyone, I was ready to conclude that harana was truly dead.

Then we met Celestino Aniel, a farmer from the province of Cavite. I can’t describe the first time he sang for us as I accompanied him on the guitar. I think the whole crew was in tears – he sang in such a heartfelt and humble way that could only come from being a true haranista. We all realized we were in the presence of great master. Then we were truly blessed to find two more amazing haranistas – one a fisherman, the other a tricycle driver.

CV:”When you do harana, you rarely get turned down.” When the harana masters are singing, there always a few shots of women as audience members, who appear to be quite touched and moved by the music. How does gender figure into the musical scene?

FA: It’s interesting because I was just reading an article about the science of music and why humans play music. It concludes that men who are able to play musical instruments advertise to potential mates that they are in top physical, emotional and spiritual shape. That’s pretty Darwinian. It is the same as the peacock displaying his plummage to advertise to females what an amazing specimen he is!

So there! Music was “invented” for courtship purposes. And that is what harana is.

CV: When you were making the documentary, what was the reaction of the local audiences? In many scenes when you perform for the audience, there are genuine interactions between you and the locals. Do the general public still feel attached to the old-school melodies and performances?

FA: There is a scene in the film when I was playing at Plaza Morga in Tondo, an area in Manila known for gangs, prostituion and poverty. It’s like the favelas in Brazil. When we set up there, we just did not know what we were going to get. Our director Benito Bautista was fantastic in connecting with the locals, making them feel comfortable in the film crew’s presence and allowing us to shoot incident-free.

Placing a classical guitarist in the middle of traffic in Manila is pretty crazy but I wanted to do it because I’ve always believed it’s a more powerful experience when you bring music to the people’s elements, as opposed to a concert hall. Most people in Tondo probably never heard of a classical musician, much less see one playing in their streets.

And their reactions was deeply humbling. Gang members were asking me to play some of the old songs that they still knew. When the crowd surrounded me and started singing along, I knew we caught a very special moment. I like to think that for those few moments, they were transported to a space where they forget about their dailty grind and hardships, and were momentarily inspired and hopeful.

CV: Could you describe you interactions with the three masters during production? What was it like? What were some eye-opening things you endured, experienced and will remember forever?

FA: We were at a beach house in Ilocos Norte. We weren’t shooting that day. I was recording the haranistas on my laptop, just basically documenting their songs. I was so moved by their singing that at one point I started to well up. I guess I was too embarassed to cry in front of these men so I had to excuse myself and headed for the restroom. I cried like a baby in that dingy bathroom.

CV:Is this film raising any awareness of the legacy? What’s at stake now to preserve it?

FA: I was at a film festival screening of HARANA a few months ago. During the closing night, it was announced that HARANA had won the Audience Award. The festival organizers said a few words about HARANA. What struck me was that they talked about the harana custom like they have known it all their lives. I mean the harana tradition, prior to the movie, was just an obscure custom nobody paid attention to, and now they are talking about the harana custom in the international stage. I thought that was an important moment – that harana has arrived.

I actually didn’t set out to create the film in order to preach preservation. And I made sure that the film does not come off preachy. It was driven by my desire to discover, learn and record these beautiful yet unheralded music. And I was expressing a reconnection to the homeland the only way I knew how – through music.

###