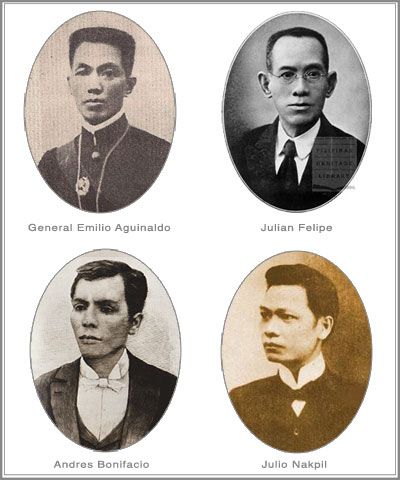

Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo (top left) commissioned Julian Felipe (top right) the official Philippine National Anthem in 1898. Two years prior to that, Andres Bonifacio (lower left) commissioned Julio Nakpil a different national anthem titled Marangal na Dalit ng Katagalugan. Why didn't any of these men consider the kundiman song form for a national anthem?

In the late 1800s, just before independence from Spain was declared, a nationalistic fervor was approaching boiling point in the Philippines. This sentiment was manifested through the popular song form of the era – the kundiman, the traditional Filipino love song par excellence.

If you think about it, kundiman, a song of admiration and longing for a woman’s love, is naturally translatable to declarations of love to the mother country. And that precisely was what the composers of the time did. The kundiman branched out from love songs to nationalistic songs.

But this was done incognito.

This kundiman served to hide its true nature – a secret battle cry with strong anti-colonialist sentiment. It allowed Spain to continue thinking that Filipinos were just singing their miserable love songs. Some claim that there were guerilla battle codes and instructions embedded in the lyrics of the kundiman songs. One in particular stood out as the favorite among the revolutionaries of the time – Jocelynang Baliwag. Officially known as Musica del Legitimo Kundiman Procedente del Campo Insurecto, it is veiled as a love song for the beautiful Josefa ‘Pepita’ Tiongson of Baliwag, Bulacan. The first letters of each stanza spells out the woman’s nickname Pepita. Perhaps that’s some kind of a rosetta stone that allows the revolutionaries to crack a secret code (it is equally possible I’ve watched too many spy movies).

There are plenty of nationalistic kundimans that are still played today. Which brings me to the most popular kundiman of all time – Bayan Ko (My Country). A classic kundiman in form and spirit, the music was written by Constancio de Guzman, with lyrics penned by National Artist Jose Corazon de Jesus, aka Huseng Batute.

Written in 1928 as a protest against American occupation, history shows Bayan Ko has been used time and time again whenever the country finds the need to defend herself from oppressors – foreign or otherwise. The song was also used against the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, who immediately banned it when he declared martial law in 1972. You can be incarcerated simply by singing it. It was not widely heard again until after the assassination of the revolutionary Benigno Aquino, Jr. in 1986. When folksinger Freddie Aguilar belted Bayan Ko in a Manila rally, it woke up the complacent Filipinos into action.

Compositionally, the genius lies in the simplicity of the melody. It is one thing to write a clever and complicated tune but it takes a genius to craft a simple melody that feels natural and uncontrived yet rich in poignancy. This is the same reason we love Mozart – his music sounds simple and unpretentious yet you’ll find plenty of richness and perfection under the hood.

Our official national anthem Lupang Hinirang (aka Bayang Magiliw) was written by Julian Felipe in 1898. It was commissioned by Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo to be used during the declaration of independence in Kawit, Cavite the same year. Performed by the San Francisco de Malabon marching band, this original version was instrumental only. There were no lyrics.

Prior to this, there was another national anthem with lyrics that was officially declared by Andres Bonifacio and the Katipuneros. It was written by Julio Nakpil with the impossibly beautiful and heroic sounding title Marangal na Dalit ng Katagalugan (Sacred Hymn of the Tagalog Republic), Katagalugan referring to the whole archipelago, not just the Tagalog region. It is unclear why Aguinaldo rejected Nakpil’s composition and preferred Felipe’s. But I would dare speculate that Aguinaldo, who is widely believed to have ordered the execution of Bonifacio and his siblings, was not a fan of the Katipunan leader who has gone “rogue” on him. He probably wanted to give the distinction to his buddy and fellow Caviteño Julian Felipe.

But that is not the issue that this blog is griping about. It is these:

Firstly, Felipe’s Lupang Hinirang is based on European national anthems such as Spain’s La Marcha Real or France’s La Marseillaise, or even Verdi’s Marcha Triunfal from the opera Aida. This reinforces the notion that we are a nation of copycats, always looking for western validation particularly when it comes to music. Filipinos already have the reputation of providing the best cover bands in the world, and we tend to patronize all kinds of music except our own. It’s a joke that our own anthem reflects that.

Secondly, our current national anthem sounds like, well European. Nothing wrong with that, but as long as we are being nationalistic, why not use our own art form? Kundiman art form is truly ours. Predating the Spaniards, its roots goes back to the indigenous art of the kumintang from the Batangas province. Kumintang is said to be a pantomime of song and dance and is similar to those of Javanese and Balinese theaters, a style that predates the Europeans’ by several hundred years.

Thirdly, and this is not a joke, the first ever lyrics of our official national anthem was in Spanish. How patriotic can you get when your national anthem uses the oppressors’ mother tongue? Whose harebrained idea was that? Apparently, it was one Jose Palma whose poem Filipinas was adopted as official lyrics in 1899. It gets worse. In the 1920s, the American colonial government ordered the lyrics to be translated from Spanish to English. In fact, there are more than one English versions. So, our national anthem consistently used foreign languages, while Tagalog was never once considered. I dread to research for a Japanese version for fear of actually finding one.

It wasn’t until the 1950s when President Magsaysay salvaged the situation by commissioning poets Julian Cruz Balmaceda and Ildefonso Santos for the official and current Tagalog version. And it was as late as 1998 with the Flag and Heraldic Code that the government declared “The National Anthem shall always be sung in the national language within or without the country”. It also specifies fine and imprisonment for violations (can we imprison Martin Nievera anyway for that horrendous version of Bayang Magiliw in a Pacquiao fight?).

Bayan Ko‘s composer Constancio de Guzman was very prolific and left behind numerous immortal kundiman and harana songs. He is himself a national treasure. The only thing of note Julian Felipe ever wrote was Bayang Magiliw, a foreign rip-off, commissioned by a friend who was a military president with blood on his hands.

Bayan Ko‘s melody and poetry never fails to stir the nationalist in our collective soul. There is no doubt that this kundiman song not only summoned our bravery but carried the Philippines towards her most triumphant moments in history.

This country rose from the shoulders of the revolutionaries. Undermanned though they may be, they have consistently fought anyone who dares to transgress the motherland. It is only fitting that we use their chosen form of battle cry – the kundiman.

——————————————————————————————————–

Music Samples

Because of the popularity of Bayan Ko, it became difficult to find a dignified version worthy of a national anthem. Most of the versions you’ll encounter in the internet are overly orchestrated and heavily arranged, with the majority ranging from bad to horrific. I am not able to get hold of De Guzman’s original score but like much of the published sheet music in the 1920s, I suspect it was originally written for voice and piano. If any readers have information on the original score, please illuminate us in the comment section at the bottom.

This is Freddie Aguilar’s version (no relations) that spurred the People Power revolution in 1986 that toppled the Marcos regime:

My own tribute to the song from the album Tipanan – A Celebration of the Philippine Guitar. It is, I’m afraid, also heavily European-influenced in style and guitar technique:

Click here to listen to Bayan Ko – Music by Constancio de Guzman

10 comments

Asin’s version is much better and more Nationalistic in tune than that of Aguilar’s

Interesting read. I agree that “Bayang Magiliw”, being a national anthem is culturally, historically, politically and artistically incorrect. And that “Bayan ko” is one of the best patriotic songs ever written. But, culturally, historically, politically and artistically speaking, “Marangal na dalit ng katagalugan” should be the national anthem.

Very interesting post! As much as Bayan Ko has always moved me, it was also originally written in Spanish. Therefore, it also “uses the oppressors’ mother tongue”. The time signature of Lupang Hinirang is 4/4, but is often played in 2/4 signature for it to be like a marching hymn. It is now recommended to be sung in acapella with the 4/4 signature, just like in boxing matches, making a slow, ballad-like effect. In my opinion, Lupang Hinirang is still a better national anthem, if we only learn it’s true meaning and history.

Another treasure find blog! 😀

I agree. Where do we sign the petition?

Facinating and well written! This is an important enough topic to debate as I was intuitively drawn to Bayan ko and found the words to the national anthem hard to sing…like trying to catch up with the music…..which in of itself is too militaristic. Nevertheless both never fails to move me and lock in my identity.

Thank you for the eye-opening article.

I always get teary-eyed whenever I sing or hear ‘Lupang Hinirang’.

‘Bayan Ko’ has the same effect on me.

I remember back in my grammar school and high school days, we would have this morning routine of singing Lupang Hinirang, Bayan Ko and Awit ng Maynila. I’ve just realized now how it fused my nationalism. However, I’ve been singing these songs without even knowing their deep background. This article gave me some thoughts to ponder….

Thanks for sharing.

Great post! I’ve always been more moved by Bayan Ko…

The singing of Bayan Ko as third anthem in some schools here in San Francisco is news to me. Thanks for the info, Ron!

The recording of Ka Freddie’s a cappella “Bayan Ko” during a dark era of Philippine history is spine-tingling. I believe many of my peers would join me in agreeing with your suggestion that this song makes for a more appropriate anthem.

Some Fil-Ams ritually sing this as the third “anthem” at Fil-Am events. For the uninitiated, many Fil-Am events begin with the “Star Spangled Banner” followed by “Lupang Hinirang.” Some groups, such as Balboa High School and San Francisco State University Fil-Grad, make the extra step of including “Bayan Ko” in this ceremonious overture.